Yesterday I swam in the Pacific for the first time this season, and I dreamed of the Atlantic shore—my childhood haunts—all night. I woke up strangely restless to take a trip I won’t make this summer: not enough money, not enough time. I’ll stay here in BC and dream of New Brunswick. No need to dwell on it. Or is there? It comes of spending an afternoon at the beach with a friend, a cribbage board, and an mystery novel. Just like old times!

As I frolicked in the waves (I can’t call it swimming), I went into a time warp, leaving behind everything but the feeling of being immersed in the sun-sparkled water. I was blissfully aware of my own body, its ability to move freely through the liquid surrounding me.

At such a moment, one encounters truth as a childish playfellow, whose simple wisdom transcends the understanding of more sophisticated, more clouded minds. What was it my best friend and fellow English teacher Ailsa told me about her son Kelly, the one who can’t talk clearly yet? To him, all liquid is “juice,” so that milk is juice, rain is juice, the sea is juice. You’re right, Kelly, I think as I luxuriate in the

amniotic ocean: I’m swimming through juice. I’m suspended in juice; I can taste it on my tongue and feel it in my hair.

And as I rejoice in my own movement, marvel at this amazing capability of my body to remain afloat in a sea of juice, I think not about myself, but about Ailsa: mother of juice boy, friend of my second youth, unwitting dispenser of wisdom.

We played tennis together on Friday, both of us struggling to hit the ball and laughing with surprise when we did. We observed no rules and didn’t keep score—and even managed to sustain a conversation for over an hour as we tried to keep the ball in volley. “Still in play!” we would shout triumphantly as the ball bounced out of limits for the umpteenth time. “I can’t remember when I’ve had so much fun!” I exclaim—and it’s true.

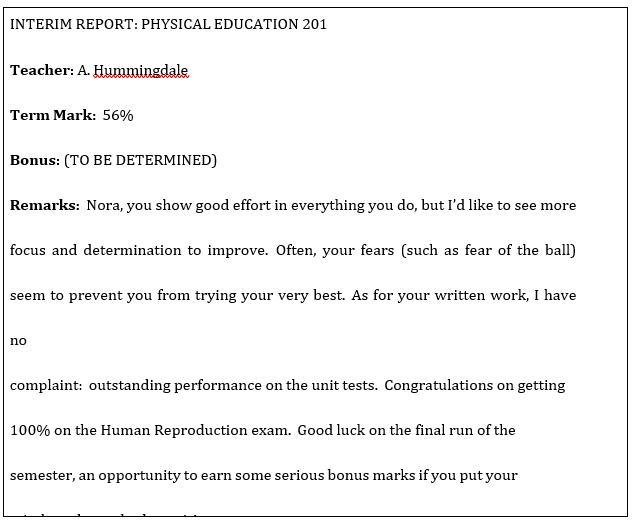

I can certainly remember when tennis wasn’t such fun: grade nine Physical Education, Phys Ed, “Fizz-Ed,” in Napanee, Ontario. And again in grade ten. The tennis unit. Eight out of fifteen, my mark for that part of the course. And I tried my best! I lament the unfairness of this to Ailsa. “Grading students based on their

athletic ability doesn’t seem right,” I tell her.

“But don’t we grade them on their writing ability?” she asks, rhetorically.

She’s right, of course.

And Phys Ed really wasn’t that bad, I guess. I could always improve my over all grade slightly by getting a hundred percent on the “health” unit: memorize the parts of the penis and you’re all set. I still think of the vas deferens whenever I hear the phrase “vast difference.” Am I still that silly teenager? The old joke, there’s a vas deferens between us…

Now, at almost thirty-five, I swim as often as I can, I go to the gym to lift weights three times a week, I dabble in yoga, I can run for twelve miles at a stretch. I’m amazed by my interest and even my ability in things physical. And this is a recent phenomenon, a part of life I’ve embraced after years of sedentary sloth, something I was driven to by the inevitable realization that if I continued to sit around I would stagnate and die. Now I realize, all those years, I was scared to try. I stuck to the things I knew I could do well—in other words, nothing physical. Last chosen for teams, berated and taunted by teammates: “Don’t be afraid of the ball, Nora!” I was afraid of the ball, I was terrified all those years: that ball coming towards me—a baseball, a basketball, a tennis ball—was my life, my own body, myself. Halley’s comet, the harbinger of doom. I knew it would destroy me on contact.

Because she was fair, after all, my gym teacher gave me a chance—the same chance she gave everyone else—for redemption. It came on the last day of classes, and those who showed up were richly rewarded for their efforts. This was the deal: for every lap around the high school’s quarter-mile track, you could earn one final mark, to be added to the semester’s total. You had twelve minutes. I had twelve minutes.

Running was not my forte, but then again, nothing physical was. Nonetheless, this was my chance to redeem myself for the eight out of fifteen in tennis, the eight out of fifteen in basketball, et cetera, et cetera. I ran like the wind, and the wind ran through me like Jackson Browne’s “Running on Empty,” a song I listened to when I was feeling that way (empty but somehow okay with it).

Here I was at the end of a dead-end semester, with nothing left to give, I thought. Yet instead of being out of breath, instead of straining my weak muscles, I found my stride almost immediately. Suddenly I knew what I wanted to find: redemption. And it was within my grasp!

I was as calm as the ocean on one of those clear, still days when the water is the mirror of the sky, and my vision—far from blindness—was as clear as if I were looking through that still water to the smooth sand bar and crusted rocks beneath, crawling with tiny specimens of marine life: snails, anemones, hermit crabs. No longer the snail, much less a stationary anemone (though most of those can glide about sometimes, it seems—they only appear to be non-motile), I was a hermit crab, scuttling, not aimlessly, but with guided purpose towards a destination.

Once, twice, three times, four times…I can’t remember how many marks I got—only that my final mark was respectable as a result of this final, redemptive effort.

That track became, for those twelve minutes, the circle of life. It’s not too late, it’s not too late, it’s not too late. And now that running has become my redemption, in my thirties, this moment resonates with particular justice, as if I can make up for years of inactivity by running with all my heart now. If so, it seems more than fair on the part of what Ailsa, with a faith much clearer than my own, calls “the Great Designer.” It was more than fair on the part of my Phys Ed teacher, dispenser of secret knowledge about that sacred organ, “the male penis” (was there a female one?), role model to teenage girls.

One day, Miss Hummingdale (Humm-bum, we called her; the other girls’ Phys Ed teacher, Miss Broadbent, needed no further nickname) told us that a new girl would be joining our class soon, and that we should treat her kindly as she might have some difficulty fitting in. “She’s a dancer at the Paisley,” Miss Hummingdale explained—a phrase which conveyed no meaning to me at the time. A few remarks from my classmates in the locker room revealed the key to this enigma: “dancer” meant “stripper,” and “the Paisley” was a seedy hotel “downtown” (if such a small town as ours could be said to have a “downtown” at all).

We walked past the hotel during our lunch hour, en route to the Uptown Restaurant on a quest for the town’s best French fries and gravy, its richest hot chocolate, its thickest club sandwich. Comfort food of the soul, sold cheap at the local diner; a dancer at the Paisley, sold cheap at the local hotel. A few doors down and worlds away from the corny atmosphere of the Superior, with its mini-juke boxes in each booth, was the dark interior of the Paisley, which we could only imagine. If there were older boys who had penetrated its inky depths, we didn’t know

them—not yet, anyway. We could only speculate about the Paisley: its booming—or would it be whining and cloyingly seductive?—music, its smoky air, its “exotic” dancers…well, any dancer would have been exotic in the how-now town of Napanee.

I don’t remember her name, perhaps because the new girl didn’t last long in our class—or in school, for that matter. Now I think what guts it took for her to come back to grade ten after being out of school, coming back to a world that must have seemed alien and fluorescent. I can’t remember her face, but I remember her body: impossibly, evenly tanned all over, her nipples protruding through the tight t-shirt

she wore without a bra. “A dancer at the Paisley,” I would repeat to myself, contemplating this exotic creature who would get fifteen out of fifteen in the tennis unit, then drop out of school.

“She’s probably had an abortion,” we whispered behind her back. We constructed an imaginary life for her, filled with one-night stands in sordid back rooms. Her refusal to wear a bra was a testimonial to a world view which was so different from ours that we simply could not—or would not—comprehend it. We never bothered—or perhaps we did not dare—to get to know, let alone befriend, the girl who joined our grade ten Phys Ed class. I may have felt sorry for her—a patronizing sentiment I’m sure she wouldn’t have appreciated. Yet I also wanted to be her—I think we all did—and to partake of her graceful confidence, her devil-may-care attitude. Yes, indeed, I thought, as Miss Hummingdale explained that “fornication” meant “intercourse”—the Devil may care about this girl, a dancer at the Paisley: how intriguing.

Now I think, she was so young. Did we give her a chance? Did life give her a chance? It doesn’t seem fair.

I think of all the second, and third, and fourth chances I’ve had in life, and I’m humbled by my own luck. I’ve always had people who loved me and looked out for me; I’ve always had places to go where I was welcome; I’ve always—through relatively little effort on my part—had my health. It seems that only the Great Designer had separated me from the dancer at the Paisley, as only now I’m separated from other misfortunes…

My friend Ailsa woke up one day a few months ago with a tingling numbness in her legs; she fears it’s MS. She fears her failing strength, she fears her husband’s obsession with jello wrestlers (we’re a long way from Kansas here–but maybe not so far from Napanee). I watched Ailsa as we played tennis the other day, looking for signs of this thing that’s maybe waiting for her silently, a would-be assassin in her own body.

What’s the lesson here, Miss Hummingdale? What’s the lesson here, oh Great Designer?

There’s no lesson, of course. That’s just the way it is: we have to keep running on course, even when the way is unclear and the heart is empty. Keep dancing as fast as you can.

Deborah Blenkhorn

Deborah Blenkhorn's stories, fusing elements of memoir and fiction, are set in Ontario, New Brunswick, and British Columbia, Canada.