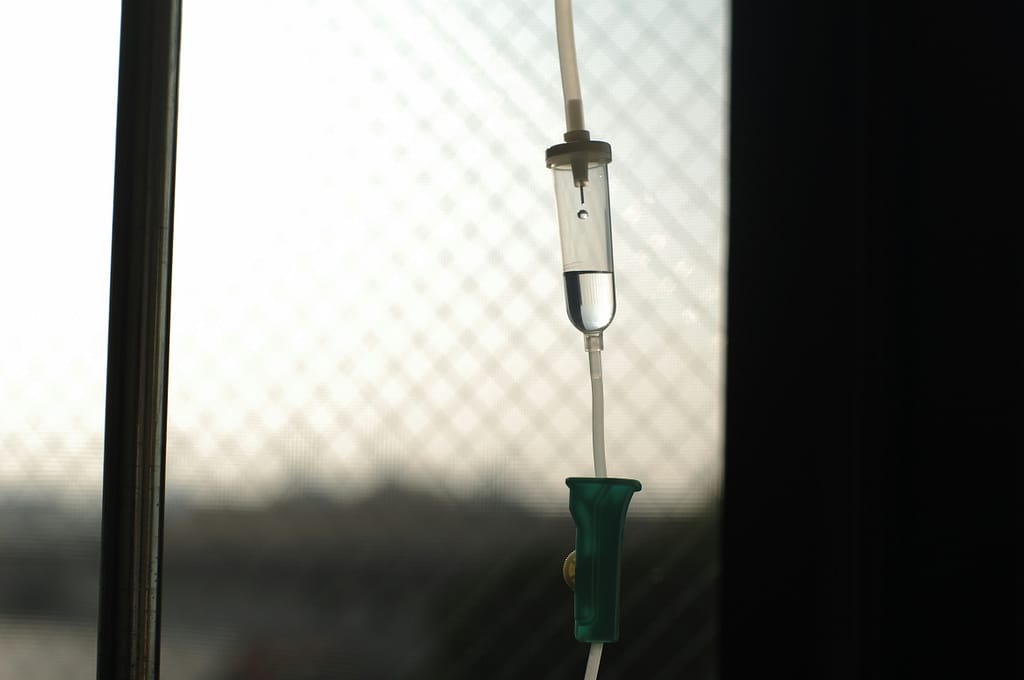

You sit there, and watch, and manage not to grimace as the nurse pierces your skin and slides the slender silver needle in your vein, purplish and puckered after she tied it off with a rubber cord to get it to wake, sleepy, like you, at this early hour. She tells you to relax and you say to yourself “yeah sure, okay, fine, why didn’t I think of that?” as she connects the IV and routinely taps a few buttons and suddenly what would be poison in any other circumstance begins to race inside the circuitous route of the tube dangling from a plastic bag suspended above your head by a shiny metal stand and then into you. It feels unnervingly cold as you trace its path up your arm before vanishing deeper.

You do try to relax, and you have been trying to relax ever since the doctor, white lab coat, typing into his laptop, hunt and peck, informed you that you needed this treatment. But it’s easier said than done, particularly when you’re not entirely sure what they’re dumping into your blood, only that it’s supposed to be a cure and at this point, when nothing has worked and it’s about damn time you start to get well, all you can do is trust that everyone knows what the hell they’re doing.

You sigh and slip on your headphones and hit shuffle on the Spotify app and let chance, or the algorithm, decide what you’re in the mood to listen to, and lean back in the rigid olive green vinyl-covered chair with the worn footrest, and close your eyes, and think about everything, and nothing, but you can’t help but wonder how you’re going to die. It could be from this disease, or it could be from something different, something completely random and unexpected: a distracted tourist on a runaway scooter, a bone in a can of tuna. It’s going to happen regardless, the one certainty, because you’re no longer young and indestructible.

It causes you to consider if you’ve done enough with your life, and you’re convinced you haven’t. But it’s always this way, each time you find yourself in this situation, more times than you deserve, your own mortality breathing on your neck, hot and stale, when you vow to do more with what life you have left, an ever-diminishing sum. But then you move on, succeeding, somehow, to increase the distance between you and death, or so you guess, and life moves on, as it always does, as it always will, until it doesn’t, and you abandon the promise you made to yourself. Not this time, you swear, as you drift off to sleep.

You have that dream again, that dream you have during periods of distress: you, trapped inside a haunted house, sometimes your own house, sometimes your house from growing up, sometimes a house you don’t recognize. You’re in this haunted house, and you’re being attacked by the ghosts that have overtaken the place. You never really see them, these shapeless, shifting spirits. You can only sense their presence, and you’re quite aware they mean you harm. So you fight them off, a battle royale, with everything you have, every bit of energy and effort, an exertion, even in your dream, like nothing you’ve ever experienced.

You fight, and you fight, and you fight. And you’re tired, and you’re beat, and you’re scared as shit of these ghosts, a near paralyzing terror. Yet you fight nevertheless. Something pushes you to persist, to keep going no matter what, and besides, there’s no alternative. You swing your arms wildly, and you kick your legs madly, and you yell, and you scream, and you curse. You struggle to exorcise these ghosts from this house, whatever house this might be, before you awaken with a startle and a gasp.

You sit there and watch as the nurse slides the slender silver needle from your vein with a splattering of crimson drops as the spiky tip emerges. She presses a cotton ball at the point of insertion and directs you to hold it in place while she tapes it down. Then she tells you, nonchalantly, as if she’s making small talk about the weather or the price of eggs, that you’re “all set” and it instantly strikes you that never has that phrase been more inaccurately applied than as applied to you at this moment because you’re anything but “all set” with a bagful of poison lurking beneath your surface.

The nurse hands you an appointment card for the next dose, like you could forget these sessions, then dismisses you to go, to return to what you would be doing if you didn’t have to spend a Wednesday morning at the hospital, to carry on as if none of this was occurring. She eases you from that awful chair that left you with a crick in your neck and an ache in your back, and leads you across the scuffed linoleum floor into the hectic hallway. You pause to acclimate to upright, lightheaded, and stumbling to regain your balance. Once you’re able, you walk down the hall past the other rooms of everyone else in their attempts to get well too, resisting the urge to peek in on any of them, and out of the building, out into the harsh, unforgiving sunlight of just another day as far as the rest of the world is concerned.

Peter J. Stavros

Peter J. Stavros is a writer and playwright in Louisville, Kentucky, and the author of the novel, The Thing About My Uncle (BHC Press). His work has appeared in literary journals, anthologies, newspapers, and magazines. You can learn more about Peter at www.peterjstavros.com, and follow on X/Twitter and Instagram @peterjstavros.